Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery:

Thoughts inspired by Not my Life (2011)

Documentary

Modern Slavery

by Reina-Marie Loader

During the escalation of the refugee crisis in Europe, this disgusting attitude of traffickers dramatically came to the fore once more. In August 2015, a truck with Hungarian number plates and Slovak text on the sides was discovered abandoned in eastern Austria. Inside, police found the lifeless bodies of approximately 70 refugees. Austria’s Chancellor Werner Faymann told Al Jazeera that there is a pressing need for all nations to work together to avoid traffickers taking advantage of the desperation of thousands of people. Speaking to a group of reporters soon after the tragic discovery, Faymann said, ‘Today refugees lost the lives they tried to save by escaping [conflict], but lost them in the hand of traffickers’ (read full report here)

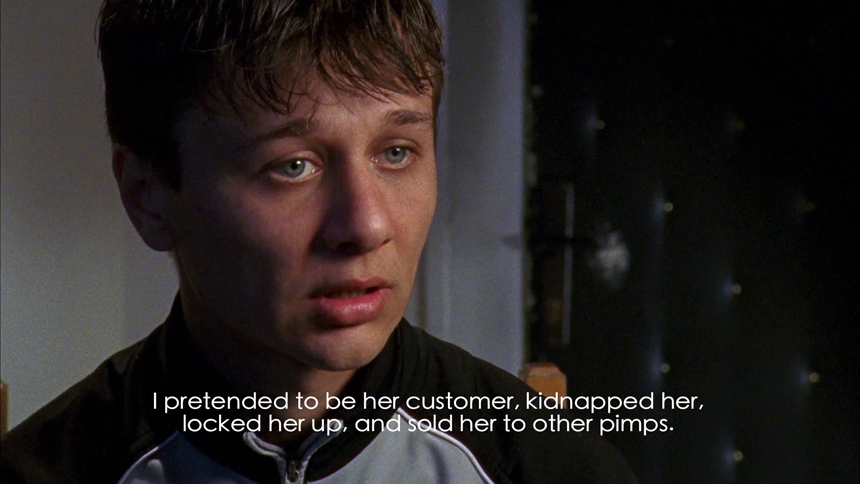

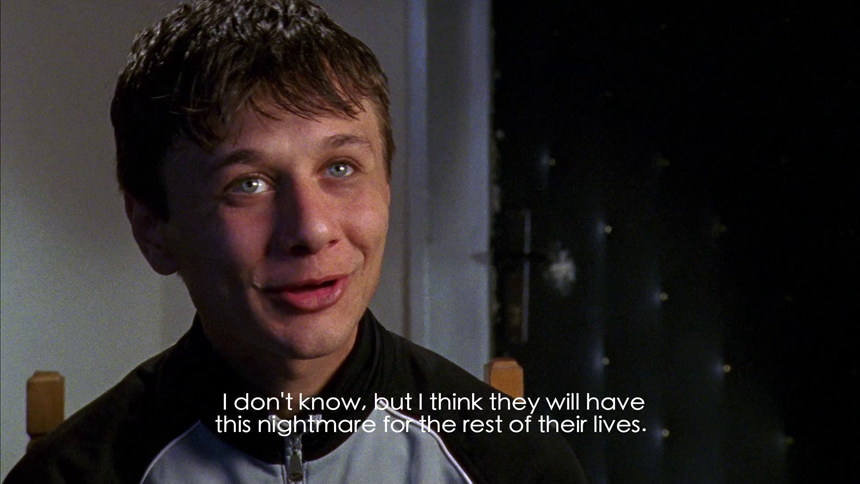

The ruthless nature of traffickers is of course well-known. Several narrative and documentary films have already highlighted that the victims of trafficking are merely seen as paycheques or objects to manipulate at will. Not my Life (2011), a documentary directed by Robert Bilheimer, succinctly illustrates to what extent traffickers are able to psychologically distance themselves from the cruelty they inflict on other human beings. Romania is one of the principal recruiting areas for traffickers, given the socio-economic state of the country. From here countless women and girls are forced into the sex industry across Europe while traffickers are rarely caught or, if they are, only receive light sentences for their actions. In fact, as is pointed out in the film, there are heavier sentences for dealing drugs than dealing in humans (see clip below). While in Romania, the filmmakers visited Zoha prison in Bucharest to interview two convicted traffickers. The first, a Turkish-Romanian man called Trian, describes his dealings in terms of an agreement, a contract of sorts between consenting individuals:

Figures 1-2

Ovidiu, the a young pimp recounting his experiences

Figures 3-6

Ovidiu explaining how he began his career

Watch an extract from his account below:

Figures 7-10

Moments of injustice across the globe

According to Free The Slaves (an NGO operating worldwide in high-risk countries such as India, Nepal, Ghana, Congo, Haiti and Brazil), this is due to the development of a global village that cannot keep up with unprecedented surges in population, migration, corruption and discrimination. They summarise the problem as follows:

d

- ‘A population explosion has tripled the number of people in the world, mostly in developing countries. In many places, the population has grown faster than the economy, leaving many people economically vulnerable. A fire, flood, drought, or medical emergency places them in the hands of ruthless moneylenders who enslave them.

- Millions are on the move from impoverished rural areas to cities, and from poorer countries to wealthier ones, in search of work. Traffickers are able to trick them by posing as legitimate labor recruiters. Migrants are especially vulnerable—they are often very far from home, don’t speak the local language, have no funds to return home, and have no friends or family to rely on.

- Global government corruption often allows slavery to go unpunished. Many law enforcement officials aren’t even aware that bonded labor, where someone is enslaved to work off a loan, is illegal. In many places, those in slavery have no police protection from predatory traffickers.

- Social inequality creates widespread economic and social vulnerability based on factors such as gender, race, tribe, or caste’. (Source: Free the Slaves).

The Slavery Industries

- Labour Slavery 78%

- Sex Slavery 22%

Gender Prefrences

- Women and Girls 55%

- Men and Boys 45%

%

Children

Figures 11

Grace, kidnapped by the Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda and used as a child soldier

Reflecting on the fate of her best friend Miriam, who is still in captivity, Grace’s wisdom shines through in a way that commands the utmost respect, given the nightmares she had to live through:

Filmography

Images

The usage of these images are purely for educational purposes. We therefore subscribe to the view formulated by Oxford Journals on their website.

Cover image: Photo by Ian Espinosa on Unsplash

Thank you so much Reina- Marie and Cinema Humain for highlighting “Not My Life” in your exceptional article. Your thoughts expressed very much align with ours, and it is very good to know there are folks like you out there working on bringing more awareness to this horrific issue. It would be great to connect sometime and discuss our shared human rights work. Thank you again!! – Worldwide Documentaries

Dear Heidi! Thank you for the lovely comment. I really appreciate it.

Your comment also gives me the opportunity to thank YOU for the work you’ve done with the film. I’ve been an admirer of Worldwide Documentaries for some time now. I too think that we are interested in very similar issues. I would welcome the opportunity very much to connect with you beyond this article. Kindest regards, Reina-Marie

This post hit hard! human trafficking is such a sensitive subject because a lot of people try to deny it even exists and turn a blind eye to it. Makes me so upset!

Absolutely! Apathy towards what other people go through is baffling!