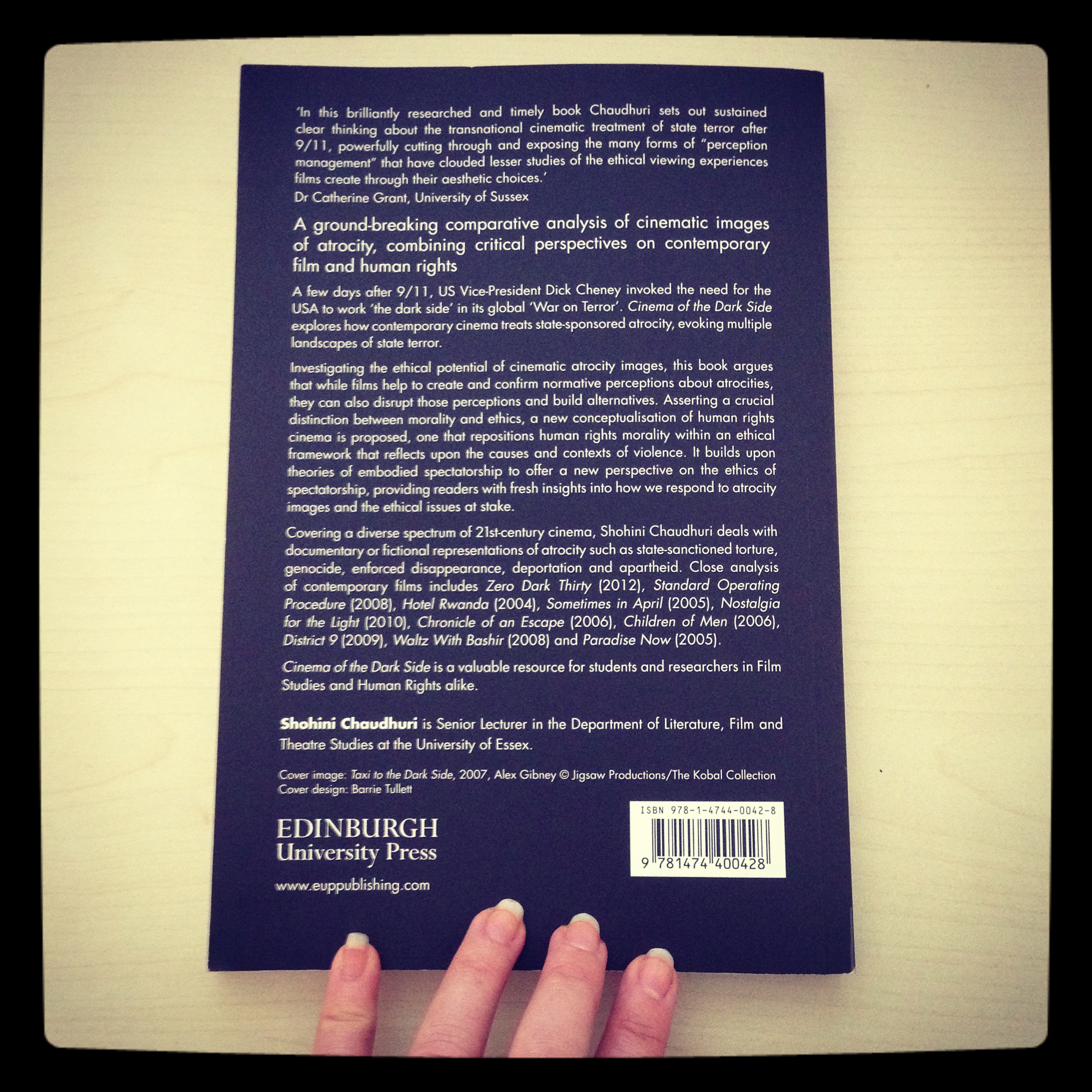

Title: Cinema of the Dark Side: Atrocity and the Ethics of Film Spectatorship

Author: Shohini Chaudhuri

Publisher: Edinburgh University Press

Published Date: 30 November 2014

Pages: 203pp

Price: £19,99 (paperback), £70,00 (hardcover)

ISBN: 9781474400428 and 9780748642632

Free Sample Copy of Introduction: Edinburgh Uni. Press

Buy: Amazone.uk

![]()

Review

g

‘Cinema of the Dark side: Atrocity and the Ethics of Film Spectatorship’ by Shohini Chaudhuri

reviewed by Reina-Marie Loader

Dr Shobini Chaudhuri’s recently published monograph entitled Cinema of the Dark Side: Atrocity and the Ethics of Film Spectatorship (2014) is a fitting start to our monthly book review series given the author’s interest in cinema’s potential to address human rights issues in a profound and ethical fashion.

The book finds its title from a statement made by Vice-President Dick Cheney following the attack on the World Trade Centre in 2001. Chaney notably declared that ‘We also have to work … the dark side’ in the attempt to keep Americans (and the world) safe from terror. The ideological conviction that is contained in such a statement not only illustrates the mindset of state-backed counter-terrorism methods, but also illustrates, as Chaudhuri notes, the impact film has on contemporary frames of reference. The metaphor of the ‘dark side’ originates from the Star Wars franchise placing good against evil, light against dark … America against the universe of terror. Given the effect films can have in shaping attitudes and language within society, Chaudhuri’s central concern is to point towards a

‘new conceptualisation of human rights cinema in which human rights morality is repositioned within an ethical framework that reflects upon the causes and contexts of atrocities, and invites viewers to question their own relation to those histories’ (2)

– regardless of where we stand in relation to those atrocities. Chaudhuri therefore points towards the need to consider the aesthetic construction of human rights cinema and its ability to shape transnational spectator engagement and awareness through embodied experiences. Consequently, as a medium with mass appeal and reach, cinema can

‘disseminate images that construct how we think and feel about atrocities. Films help to shape prevailing normative perceptions, but they can also question those perceptions and build different ones’ (2).

While factual depictions of historical events are of course important, the book argues for a more encompassing view of the meaning of cinema within a human rights context – namely that it could go beyond mere factual and/or witness accounts. It can critically consider how mindsets and social frameworks create ‘moral’ platforms from where atrocities can occur not only within national borders but also on a global scale. In this regard, Chaudhuri makes clear that the book considers films specifically made for transnational audiences. In other words, they are made for spectators, who are not necessarily directly involved in or affected by the atrocities represented in each film. Chaudhuri however does not regard this in a negative light as human rights film criticism often does, but sees the potential to effect change in an ethically rather than morally driven way.

A clear distinction between ‘morality’ and ‘ethics’ is thus pivotal to Chaudhuri’s approach throughout the book. On the one hand, ‘morality’ refers to values constructed by socially formed laws, codes and conducts, which are fluid concepts able to adapt to specific circumstances. The morals of individuals within society can therefore be manipulated by the state through laws, the media and language. ‘Ethics’ on the other hand, involves the climate in which morality is formed – it is a ‘meta-reflection on the moral framework’. In other words, our ‘morality’ is conditioned by our society and the state, while our personal ethics can question, change and/or develop those moral attitudes (14).

Leading on from this, Chaudhuri argues that mainstream media and Western capitalist policies restrict viewer engagement with human rights infringements by framing atrocities from a highly controlled perspective that largely neglects their political and colonial origins. The new human rights cinema for which Chaudhuri presents a convincing argument can counter such a restriction by offering viewers an accessible, yet altered perspective on mainstream rhetoric. As a visual medium that makes us think as well as feel, cinema is in a unique position to do this.

Furthermore, although the book focuses on films produced in a post 9/11 climate, the author does not exclusively deal with the effects of terrorism. The acts of atrocity on which the analysis centres, are those associated with ‘state terror’, which cultivates a climate in which ordinary people may be led to commit terrible acts. State terror, it is argued, destroys lives in a silent and understated fashion, where ordinary citizens either join in, say nothing or turn a blind eye – which in many ways reflects how we receive films about atrocity. However, Chaudhuri cautions that films seeking to highlight this dimension of atrocities, should be wary of soft-coating acts of terror by transforming individual perpetrators into victims of state oppression.

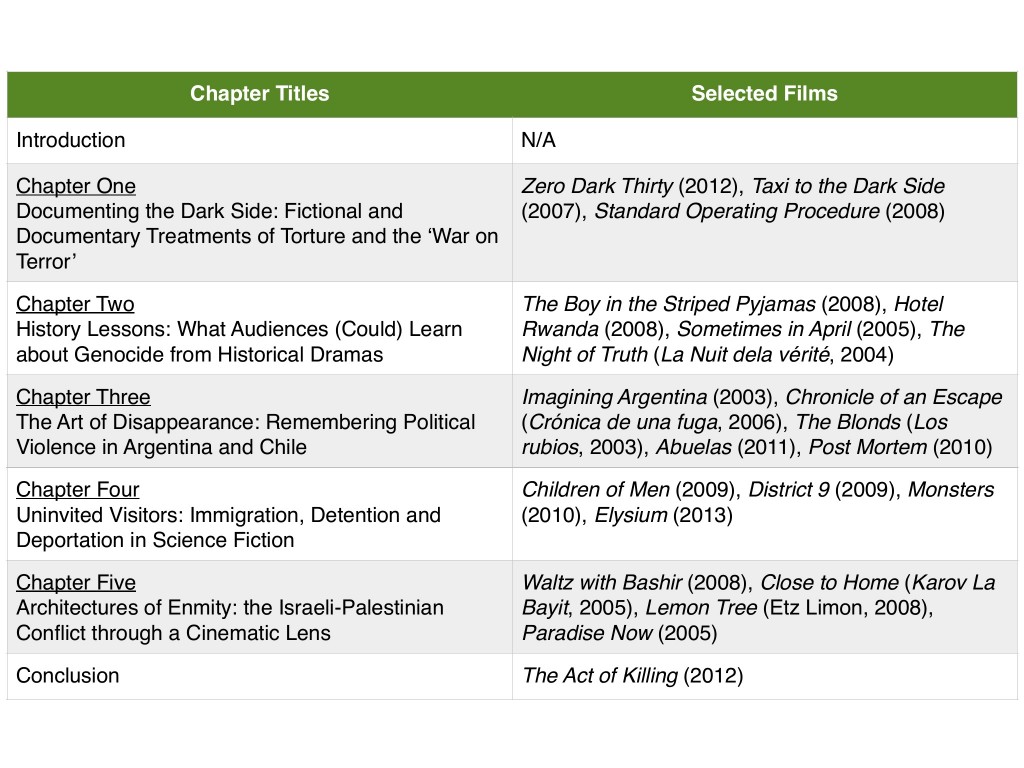

Chaudhuri isolates five specific forms of state terror, which also structure the book into five chapters. These are torture, genocide, enforced disappearances and population displacements/apartheid. Each one of these state-sponsored acts are, according to Chaudhuri, remnants of a continued legacy of colonial pasts as maintained by contemporary politics. The ethical and moral implications of representing such issues through the visual medium thus forms a core dimension of the book’s interest in film spectatorship.

Theme: The transnational representation and reception of images of atrocity within a post 9/11 context.

Thesis: Films are in a unique position to create what Chaudhuri calls ‘affective thinking’, which in turn can challenge dominant and oppressive thought patterns. From this perspective, cinema can be a more profound form of critical involvement than simply thinking about the issues themselves. Cinema’s aesthetic nature thus allows us to think as well as to feel, which provides the opportunity to look at our own rights and those of others from an ethical position rather than a more problematic moral one. Importantly however, as Chaudhuri states,

‘…instead of looking away from cinematic atrocity images, we should look on, yet learn to interpret them differently, and foster more critical forms of human rights representations as the basis for breaking oppressive patterns of thinking and behaving.’ (183)

In the following sections below, a summary of each chapter is provided. Click on the tabs for more information:

A particular strength of the whole book is Chaudhuri’s ability to contextualise her discussion within a contemporary as well as historical framework. This is impressively apparent from the outset of the book in that Chaudhuri structures her main argument around a social and political discussion of environments that cultivate moments of atrocity. Chaudhuri aptly places film (and particularly the media) within this environment – a dimension consistently developed in the subsequent chapters. Additionally, Chaudhuri offers valuable insights related to debates around human rights cinema. In this regard, human rights cinema is discussed from an activist’s perspective as well as from a film studies perspective. Throughout, Chaudhuri interacts with significant critical figures. In this chapter, thinkers such as Hannah Arendt (banality of evil), Gilles Deleuze (embodied spectatorship), Slavoj Žižek (modes of violence) lend a pragmatic starting point to a complex area of research. Finally, film’s role as an affective medium with the potential to cultivate insight and change is saliently introduced.

Documenting the Dark Side: Fictional and Documentary Treatments of Torture and the ‘War on Terror’

Chapter One focuses on the concept of torture and how films dealing with this form of human abuse are often confronted with questions related to truth. Through her discussion of films about the controversial use of torture by the United States, Chaudhuri suggests the need to redefine what ‘truth’ means within cinema. Drawing on documentaries that rely heavily on photos as evidence, this chapter’s main thrust angles towards placing greater value on the aesthetic choices in atrocity films as this may not only lead to knowledge, but also insight. By means of the various cinematic devices including editing, Chaudhuri argues ‘that moral and ethical perspectives emerge.’ (33). Additionally, Chaudhuri cautions against the tendency of cinema (and particularly fiction films) to manipulate narratives thereby ultimately asking audiences to approve torture as a necessary evil. Finally, and probably most significantly, Chapter One highlights the fact that cinema is often regarded as existing in a vacuum, while in fact it is in a direct relationship with ways in which acts of atrocity has been framed historically. Here, Chaudhuri argues that torture as a human rights issue directly relates to a colonial past, dressed in sheep’s clothing.

History Lessons: What Audiences (Could) Learn about Genocide from Historical Dramas

In Chapter Two, Chaudhuri deepens the discussion on the colonial background of atrocities by referring extensively to the work of Hannah Arendt – particularly her thoughts on totalitarianism that later became known as Arendt’s ‘boomerang thesis’. To illustrate this point within film, genocide is underlined as a recurring crime that effects many nations since the Second World War. The global implications of genocide are brought to the fore in this way. As a result, issues related to national and international complicity form a significant part of this chapter’s argument and is well-illustrated by the films selected. Furthermore, Chaudhuri highlights that human rights cinema allows us to negotiate with past genocides from a contemporary perspective with the hope to prevent them in the future. This is important for the chapter’s argument, since genocide and atrocity ‘are not just about the past but hold implications for present-day society, with the need to find ways of breaking deadly repetitions of violence’ (83).

The Art of Disappearance: Remembering Political Violence in Argentina and Chile

The next section of the book focuses on a highly underrepresented area of discussion, notably enforced disappearances of people in Argentina and Chile. Particularly appropriate to the book’s overall scope is this chapter’s perspective on disappearance as a metaphor for the memory and/or amnesia of these events. In this regard, Chaudhuri refers to what Michael Rothberg calls ‘multidirectional memory’ (89), which suggests once more that atrocities and their impact do not exist merely within the context of those nations affected. They spill over into a global environment, which has the potential to create solidarity between nations. We can therefore not only be complicit in creating atrocity, we can also be complicit in creating positive change by means of such a cross-cultural exchange through memory and film. Deleuze’s time-image finds particular relevance in this chapter given the films selected – many of which create sensory experiences breaking away from conventional representations of atrocities.

Uninvited Visitors: Immigration, Detention and Deportation in Science Fiction

Chapter Four presents a deeply engaging discussion of science fiction’s role in creating meaning and cultivating understanding about human rights abuses such as racially framed population displacement/apartheid. Chaudhuri sees science fiction as a ‘historiographic mode’ with mass appeal that allows mainstream audiences to understand their current placement in relation to the past. Science fiction creates alternative worlds through deliberate attention to mis-en-scène. The strangely familiar visual environments that films from this genre tend to create thus have the potential to remind viewers of actual past atrocities. As such, science fiction films create the opportunity for global audiences to comprehend the longevity of such crimes. Apartheid is not a crime that is contained in one act of cruelty. It is a social and often media-saturated ideology that creates a climate of acceptance and normality. The prolonged ‘dehumanification’ of certain sections of society thus becomes a core aspect of Chaudhuri’s argument here – one which is carried through and developed significantly in the next chapter.

Architectures of Enmity: the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict through a Cinematic Lens

The final chapter presents one of the most overtly critical chapters of the entire book. It presents the reader with several arguments problematizing dominant representations of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In this regard, Chaudhuri points out that numerous films, most of which are produced from Israeli perspectives, seek to redress the conflict by making victims out of Israeli soldiers in Lebanon. Conversely though, films that are more concerned with understanding the actions of Arab suicide bombers are often criticised by the general public for ‘humanizing’ terrorists. She specifically isolates Folman’s animated film Waltz with Bashir as an example of an Israeli film seeking to create an identity of victimhood that covers up Israel’s ‘brutal actions’ in Lebanon. Although Chaudhuri makes sound and convincing arguments in relation to how skewed Israeli-Palestinian conflict representations are, Folman’s film is perhaps somewhat more complex than Chaudhuri’s analysis suggests. Moving on from this, Chaudhuri usefully examines the concept of the ‘other’ and their systematic dehumanification by the media and society. In this regard, the victim-perpetrator dynamic is stimulatingly framed in relation to gender and traditional concepts of the gaze.

The conclusion is clear and concise and only consists of six pages. Still, it presents the reader with a good summary of the overall arguments contained in the bulk of the book. Chaudhuri includes a final discussion of Oppenheimer’s film The Act of Killing, which sits somewhat uncomfortably within the framework of a conclusion, but is nevertheless interesting and thought provoking.

Cinema of the Dark Side is a very exciting addition to the human rights cinema canon. It presents the reader with a dense range of critical text, while impressively introducing new thoughts that could potentially move both practice and theory in a new direction. It is extremely well researched and argued, while simultaneously remaining accessible to a wide readership despite the complexity of the subject. It shows a respect and sensitivity to human dignity, which supports Chaudhuri’s main argument for a more ethical yet critical form of human rights cinema. Chaudhuri argues for an emphasis on the artistic choices made by filmmakers in order to push the analysis of human rights films in a fresh direction. Given this core statement, there could perhaps have been some more emphasis on close sequence analysis where films could have been discussed in relation to specific moments. At times the discussion of the films themselves only touches the surface of mise-en-scène and other meaningful directorial choices. This is however only a small issue and does not detract from the importance of this book’s contribution. It would especially be an excellent addition to any film course, since the way in which the book is written describes complex notions in a concise and easily understandable way. What is more, given the nature of this work, it can certainly also form a core resource for students and scholars from other disciplines.

Very good review. It made me want to read the book.

Thank you.

Hello there Jossi! Thank you for your comment. I am glad it had that effect on you. It really is an interesting read. You can’t go wrong 🙂