Student Essay

Problems with Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan (1998) as an Anti-War film with claims to authenticity

by David Rosenberg (University of Vienna student)

Steven Spielberg has an exceptional ability to display and manipulate the whole gamut of emotion within his body of work. As much as I admire this craftsmanship I would suggest that his approach is rather unsuitable for films that are based on historical events – but especially for films depicting war such as in the case of Saving Private Ryan,

Not in the least, because to achieve that effect of affection he tends to stage the parties of conflict in a binary way – one side of a conflict in a very positive, almost mythologically elevated way (Heroes like Indiana Jones, Schindler, The Allied „Brothers in Arms“) and the other side composed of stereotypical Nazi villains and other one-dimensional antagonists that do not seem to be a likely representation of any war that actually happened. As Tim O`Brien states in The Things They Carried : “the only certainty [of war] is overwhelming ambiguity. In a war you lose your sense of the definite, hence your sense of truth itself, and therefore it’s safe to say that nothing is ever absolutely true” [1]

But in the case of war films like Saving Private Ryan there are not many ambiguous representations of war, quite the opposite. The viewer gets confronted with many simple truths about historic events that are re-enacted in ways seeming very authentic through various film techniques that eventually became a new standard for the depiction of war films (generally imitating the imagery of combat cameramen with less-saturated film stocks, lenses without glare-reduction coating and shaky hand-camera movements). [2]

In most cases it is probably not a very safe point of departure for the critique of a film or a director to point out that a film lacks some kind of ambivalence in its depiction of historic events, because no matter how concrete the inspiration for that film may be, it will still be a fictional piece of art and the personal viewpoint of a director. Critique based on that may seem like a personal dislike of the critic.

Yet in the case of a director as influential as Steven Spielberg, it gets more difficult in my opinion. He is capable of reaching huge audiences with topics usually not deemed entertaining enough to attract huge crowds and in a way forms a new standard of how things are done and depicted in Hollywood. Still, it’s not a severe crime to make very successful blockbusters. BUT at the point where that director openly declares that his intentions with his serious films are to educate in a moral way [3] and manages with all his influence and medial coverage that his point of view is considered the only right one, and perspectives on his films that differ from his are considered wrong – at that point I think it gets an immoral aftertaste, especially if some of his personal statements and ideologies shown in his films do not seem to be morally above doubt. Again, films probably shouldn’t be judged on a moral basis, but since this is an essay and not a scientific report, I hope it is applicable for the issue I am addressing about film.

To exemplify this theory of Spielberg and his PR-department as a kind of moral censor, I’d like to refer to a media event that occurred after a group of high school students were kicked out of a screening of Schindler’s List in 1994. Following a scene in which a KZ guard executes a Jewish prisoner in cold blood and for no apparent reasons one of the students allegedly said, “Oh man, that was so cold!“, and some other students laughed at that remark.

That incident was enough to stop the screening of the film and led to a series of articles in the U.S. media interpreting this outburst of one student as an indicator of the immorality of American youth. It was not seen as a teenager’s renitent act of disobedience or the attempt to come to terms with a horrific scene by means of laughter or even as a way to express criticism about the way this murder is depicted. It was only seen as a moral failure, laughing at the sight of murder – as if that were the only possible interpretation of the incident.

The teenager’s actions were described by newspapers as “contemptuous,” “insulting,” and “ethnically insensitive.” [4] The reporters who regularly went to the students’ school after the incident asked the students questions such as whether they thought that the Holocaust was funny, if they were anti-Semitic or if they lacked compassion for the deaths of others. Spielberg’s reaction to this incident was “to finance a multimillion-dollar high school Holocaust-curriculum with Schindler’s List as the pedagogical centerpiece. No worries, he comforts; those youth too anemic to absorb the message of the film during their initial viewing soon will see it again. And again. And again.” [5]

The reporters’ questions imply that it was obvious to the reporters that the students laughed about witnessing a death, not about a filmic depiction of it.

In Time [Spielberg] is reported as having instructed his cast, “we’re not making a film, we’re making a document.”

This is perhaps the most pernicious notion that has become attached to Schindler’s List that it is somehow more than a movie, more than a simulation: that it is “the real thing”. Yet to confuse any aesthetic representation with the object represented is either to participate, or to be lost, in a lie. [6]

Spielberg and many critics seem to be lost in that lie and take the film as “the real thing” and therefore seem to think that if a person doesn’t emotionally react the way it was intended by the director, there is something fundamentally wrong with that specific viewer.

A similar reaction was triggered when Saving Private Ryan was discussed in a less than affirmative way. Critiques were mostly positive and praised the film for its realism, its “bloody authenticity” [7], the technical artistry of Spielberg and his cameraman Janusz Kaminski and generally “for getting it [WWII] right” [8], while at the same time bashing possible attempts to criticize the film. Everyone who isn’t moved by this film has to be one of the cynical “media-savvysmartasses” [9]. This seems to show a resemblance to the incident with the high school students.

The thing that irritates me the most, however, is the fact, that pretty much all the reviews praised Saving Private Ryan as a genre defining ANTI-war film, and that seems to be incommensurate with the less positively discussed framing of the film. If the epilogue and the prologue as well as perhaps the last third of the film leading up to the epilogue were cut, I could agree with that position – then it would be a film about good, honest and brave men trying to accomplish their mission, with which they don’t agree in the first place, in order to get back to their civilian life. The brutal and authentic-seeming fighting scenes that show human beings as mere meat sacks being annihilated in various ultra brutal ways, could substantiate the notion of regarding Saving Private Ryan as an anti-war film, essentially a rather conventional but not really genre redefining anti-war film with flabbergasting fighting sequences.

But since those other scenes are in the film, I have a severe problem to accept the labeling of this film as an anti-war film. The film only disguises itself as one with a critical perspective towards the violence and the brutality of war. Saving Private Ryan is the cornerstone of New Hollywood War films “that use visual realism to disguise heightened moral assertions”. [10]

It glorifies the men who took part in that war as heroic martyrs who ultimately act against their articulated dislike of the insane seeming mission and try to hold an important bridge against superior German forces because it might be “the one decent thing” they do in this war. With this suicide mission they decide to make something noble out of their war efforts and make, as the title of the film already suggests, war seem to be about saving people and not actually killing people, which is in my opinion not a very strong argument for an anti-war film.

I want to take a closer look at some scenes in the climactic battle for the bridge to exemplify why Saving Private Ryan is not the widely acclaimed genre defining anti-war film, but a technically well disguised glorification and justification of war.

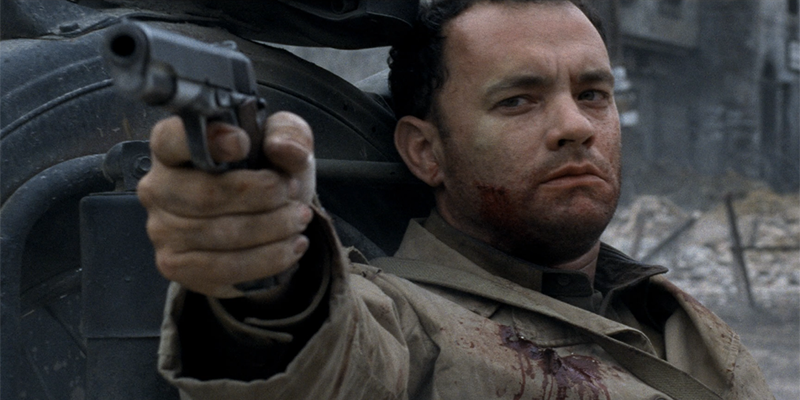

When the squad finally catches up with Ryan near the city of Ramelle, they don’t seem overly excited at the sight of their mission’s goal, Private Ryan. The expectations of him are quite high, various members of the squad articulated that “he’d better be worth it” several times already and the young Private Ryan doesn’t seem to fulfill these expectations satisfactorily. Then Captain Miller explains their mission to Ryan and that his brothers all died. Instead of going with them, Ryan protests against his being saved, which angers the squad and they aggressively confront him with the fact that two soldiers already died because of him. (See picture 1)

Figure 1

Ryan wants to know their names in order to remember them and makes his speech about why he can’t abandon his post and why he openly refuses to follow his superiors’ orders. He argues that he won’t comply because he didn’t deserve to be relieved from his post any more than his fellow soldiers. He points to his comrades and the camera shows us three battle worn soldiers, none of whom will survive the following German assault on the bridge, in medium shots and medium close-ups.

When asked by Captain Miller what he should tell his mother on receiving the likely news of his death, he replies:

“Tell her [Ryan’s mother] that when you found me, I was here and I was with the only brothers that I have left, and there’s no way I was gonna desert them.”

This scene and the speech makes the squad and the audience realise that Private Ryan is potentially “worth it” because he holds up the right ideals – camaraderie and sense of duty – even if upholding these ideals mean his likely death. His selfless self-sacrifice is what makes the squad join his effort to hold this bridge because he is willing to risk his life for his “brothers” the same way the squad members were risking theirs for his – which makes him one of them and therefore worth saving.

To have that kind of family bond, this feeling of a brotherhood, with the notion to “never leave a soldier behind” makes sense for any military institution, but to depict soldiers in the way the U.S. Army would like to see itself (at the same time giving away how it indoctrinates its soldiers) hardly qualifies as a critical approach towards war. Spielberg manages to send a mixed message about war – on the one hand he shows the brutality and violence of it, and on the other hand he makes the deeds of the American soldiers look even more heroic because of this violence. The battle for the bridge seems to go in a similar direction, the squad and Ryan’s paratrooper division face numerically and materially highly superior German forces (according to their scout 50 soldiers plus “change” and 4 tanks against their roughly 15 soldiers, 2 machine guns and explosive socks) and they successfully hold them back for quite a long time. Unfortunately, that battle is depicted in a way that is contradictory to the film’s appraised fighting realism; until the Allied reinforcement arrived I counted 14 hits or explosions that very probably killed or rendered American soldiers defenceless, while the German forces are seen to suffer 56 wounded or killed soldiers and three tanks destroyed (I only counted on screen hits or explosions with visible impact). [11]

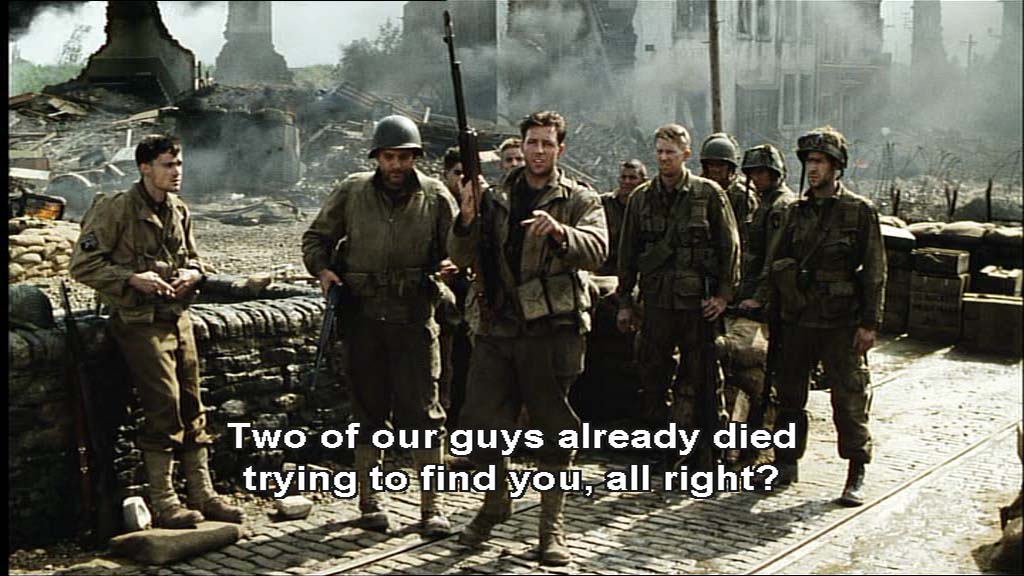

Of course it is possible that there were even more soldiers on the German side whom the scout couldn’t see, so quite possibly the odds are even more unlikely, and it all seems like the “miracle” Sergeant Horvath was hoping for. On top of that, the German soldiers (amongst them many of the allegedly elite military force of the Waffen-SS) are fighting in such an ineffective way that the battle for the bridge seems as realistic as a conventional “us vs. them” John Wayne western. The soldiers often fail to take cover and run pointlessly straight into the line of sight of the American soldiers (See Picture 3). The Americans also seem to be superior marksmen, as when the G.I.s retreat from one side of the bridge to the other, the Germans manage to fail landing a single shot, even though they are shooting from a significantly closer position and are in the majority. (See Figure 2)

Maybe Spielberg was aware of that latent similarity himself because he lets Captain Miller name the last point of defence “The Alamo”, which is not only a possible reference to an American history event, but also the title of John Wayne’s only directorial work that is also famous for its rather unveiled jingoism. But where Wayne justifies his historical American war with ideals of freedom and justice, Spielberg justifies his with nothing but sentiment. This omission of politics about a very political event makes Saving Private Ryan somewhat arbitrary – when Spielberg shows soldiers fighting for their brothers in arms and for their return to civilian life, one could easily transfer the film to the other side of the front and show a group of unpolitical German soldiers who try to rescue one of their own.

Although I doubt that such an imaginary film, let us call it “Die Rettung des Gefreiten König”, depicting war in the same kind of “reality”, would be appraised for getting the fighting scenes or the brutality of war right. Of course Spielberg has a rather safe moral vantage point from a contemporary Western perspective, since it is a safe assumption that the world is better off with the Nazi aggressions in Europe stopped through the intervention of the Allied Forces. He assumes it to be a truth universally acknowledged that the Allied soldiers had the right ideological reasons to fight, so he only focuses on their emotional motivations to commemorate that noble effort of this generation.

Yet with the use of an accumulation of dramatic scenes, he also manages to make the audience, as it were, cheer Upham on when he executes an unarmed German soldier, again an incident that evokes acceptance as something that it is not and that is difficult to challenge morally. This scene doesn’t show this execution as a moral failure on Upham’s side but more like a redemption for him, a scene where he finally “mans up”. For me, it is one of Spielberg’s most signifying, in this case almost sinister, film tricks that he is capable of triggering an emotion against the viewer’s will.

In this scene, I assume, his intention is to jerk some tears out of the viewer or just to touch the audience emotionally by having some kind of redemption for Upham’s previous cowardly actions. The German soldier he executes, commonly dubbed as “Steamboat Willie”, is the same one he defended earlier in the film. He appealed to Captain Miller not to execute him to avenge Wade’s death. He said “it is not right”, “against the goddamn rules” and Reiben guesses “that was the decent thing to do”.

I generally don’t have a problem with being emotionally involved in films but in this scene it feels like watching some kind of emotional porn, feeling ashamed or betrayed by my physical and emotional reaction as if I were witnessing a rape and getting an erection. I know, that I intellectually do not agree with what is happening on screen, but because we follow the action of that film in such a simplified clear way, it feels almost impossible for me to not react emotionally as I get overrun by this emotional avalanche that consists of the slow motion kills of the G.I.’s we are supposed to like by now:

We see that Upham is directly responsible for the death of Mellish by not helping him fight off the German soldier with whom he is in a close combat situation. When that soldier gets out, Upham is too terrified to act and the soldier apparently determines that he is not worth killing. Then Upham sees how Steamboat Willie shoots Captain Miller, who is fatally wounded but keeps on fighting, and when the “cavalry” finally comes to save the day in the form of the long sought reinforcement and air support Upham jumps out of his hiding space, shouts “Hands up” to a group of German soldiers, shoots Steamboat Willie and lets the others go.

Not only is this scene rather implausibly staged – the German soldiers have clear shots at him (Picture 5) and eagerly follow his instructions, while another soldier just needed one glimpse to determine that he is not really a threat a couple of minutes before (See Picture 4 and 6) – but it tops this emotional dramaturgy with making Upham look like a saint.

After he shoots Steamboat Willie (and the music tunes in) the camera films him against the sun and we see rays of light coming from behind his head, looking like a halo (See Picture 7). After that spiritual redemption scene Miller calls the Allied air support “Angels on our shoulders” and before the battle at the bridge Reiben and the religious sharpshooter (who cites Bible quotes between his killings) have a rather un-ironical discussion about having God on their side. So apparently they are not only decent Everymen, they are almost saintly figures, who happen to fight for the side God is on. The critic Roger Ebert wrote, that for him this scene is one of the key performances because “his [Upham’s] action writes the closing words of Spielberg’s unspoken philosophical argument”. [12]

I wonder what that philosophical argument might be, if spoken, since to me it seems to be a rather distorted humanistic viewpoint. In this film there is a fine line between saving people as doing “the decent thing” and killing people as doing “the decent thing” with the only defining distinction between these decencies in the nationality of the saved or killed person.

Or is the message supposed to be that war is not the place for humanistic beliefs anyway, exemplified by letting Upham “man up” by abandoning his humanist ideals shown earlier? There are hardly any films that personally agitate me as much as Saving Private Ryan, and somehow it offends me morally to the point of indignation that this film is widely accepted as the modern masterpiece in the anti-war genre, while to me it is a nationalistic glorification of war that inspires self-sacrifice of young men and stresses the importance of camaraderie in a way that would make any propaganda filmmaker jealous. I have problems rationalising my strong negative feelings about this film, but I think it has to do with that moral claim of authenticity as well as Spielberg’s tendency to ask seemingly difficult questions only to subsequently give easy, comforting answers himself. Not to mention the questionable virtue of turning tragedies into success-stories – not simply economically but also through their content by making the Holocaust about saving Jews and WW II about saving lives. This makes Spielberg’s films too eager to please the audience for me to take them seriously as the moral guidelines they are sold as.

The dying words of Captain Miller to Private Ryan and the audience are “earn this” and the questions repeatedly asked in the film, whether it is right to sacrifice the lives of many for one life and whether Ryan “earned” their sacrifices, are answered affirmatively, not only literally by Ryan’s wife, but also by Spielberg’s filmic depiction of war, that shows us that “the life of an American Everyman does in fact justify […] war”. [13]

Notes

2. Cf. GATES. p.300. cf. PEEBLES: p.48.

3. MILLER. p. 707

4. Quoted from MILLER. p. 707. F

5. Ibid. p.708.

6. Gourevitch, Philip, “A Dissent on Schindler’s List”, in Commentary, Feb. 1994, Vol. 97, p. 52. Quoted After NORRIS. p.106.

7. MASLIN

8. WOLCOTT, James, “Tanks For The Memories”, in Vanity Fair, Aug. 1998, pp. 70-76 . Quoted After CARSON

9. Ibidem.

10. GATES. p. 298.

11. There is a Wiki Page dedicated solely to this film that counts about 75 dead on the German side. I don’t know how trustworthy that source is, but I’d like to point out that the articles there are written in a way that treats the actions on the screen like a historic document. http://savingprivateryan.wikia.com/wiki/Saving_Private_Ryan_Wiki last accessed 20.07.2015. 10:50

12. EBERT.

13. PEEBLES. p.52.

Bibliography

Carson, Tom, “And the Leni Riefenstahl award for rabid Nationalism goes too… A reconsideration of Saving Private Ryan” in http://www.esquire.com/entertainment/movies/a1490/riefenstahlnationalism-0399/ last accessed: 14.07.2015. 12:38

Ebert, Roger: Review of Saving Private Ryan: http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/saving-private-ryan-1998 last accessed. 20.07.2015. 14:19.

Gates, Philippa: “’Fighting the Good Fight’ The Real and the Moral in the Contemporary Hollywood Combat Film”, in Quarterly Review of Film and Video, Vol. 22. No. 4 (2005). pp. 297-310.

Maslin, Janet, “Panoramic and Personal Visions of War’s Anguish”. in NY Times 24.07.1998, http://www.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9C01EEDF1239F937A15754C0A96E958260 last accessed 14.07.2015 12:54

Miller, Reid, “A Lesson in Moral Spectatorship”, in Critical Inquiry, Vol. 34, No.4 (Summer 2008) pp. 706-728.

Norris, Margot: War in the Twentieth Century. University Press of Virginia (2000).

Peebles, Stacey, “Gunning for a New Slow Motion.: The 45- Degree Shutter and the Representation of Violence”, in Journal of Film and Video, Vol. 56. No. 2 (Summer 2004) pp.45-54.

If the writer of this was an experienced world war ii veteran, than I might try to agree. If the writer has never seen war world ii, or any war for that matter, THIS ARTICLE, THIS ESSAY, THIS COMMENTARY ARE FICTION AND COMPLETELY MEANINGLESS. If this writer thinks that their resources & research somehow justifies that readers should disregard Spielberg and hollywood, because some writer who had never experienced the situation has some moral high ground?? I doubt it, and I despise the concept in this opinion. Did this writer really research in interviews and testimony of those directly involved to determine what may have happened in world war ii?

Its been over a year since this was posted, but i have to say, it struck a chord in me. On my initial viewing of Saving Private Ryan, something had irked me; something didnt seem right about the film. Everyone said it was a masterpiece and how it had a very important antiwar message. Now, i’m no movie reviewer or anything, but in regards to the message this movie is said to send, it didnt really do it for me. Coming out of the film, little told me about how bad war is. I just thought the sniper dude was cool. It felt like a glorification of war, not a statement about the horrors of it. Now, im 19 this year, so i know little about the horrors of battle. I feel, that if Saving Private Ryan really wanted to send out an anti war statement, it shouldnt do it by showing how heroic everyone is. It should do it by showing how hopeless their efforts are. I know that people say how the movie made them feel how bad war is, but if anyone were to wonder why young people these days have problems believing the terrors of war, honestly, i think its because moviemakers glorify war too much.

Tldr: people who direct war movies glorify war too much, and thats why young people (like me) think war is cool.

People shouldnt be shocked by how badly we react. They should be shocked by the bad decisions made by these moviemakers and stop watching these movies with a veil of how they were affected by the tragedy that is war.

Thank you, Albert, for a very thought-provoking response to the point Rosenberg is making in his analysis. I agree with you and share your criticism of the film. On my original viewing of the film, something did not sit well with me either – but I marvelled at the skill and technical mastery of the film. However, I think audiences generally approach the film from a historical perspective – i.e. the historical fact that WWII needed to be fought and was indeed fought for the right reasons. Subsequently, they are dazzled by the craftsmanship of the film and do not see the problems with its message. Viewers thus unfortunately neglect to consider that the film is made long after the world war was fought. So the ideological perspective is significantly different. America has fought many a war since then (and many of them for the wrong reasons). In the case of ‘Saving Private Ryan’ the contained ideology should therefore be considered critically for several reasons – but most importantly, because it frames war as a right of passage where young boys become men. The sentimentality and ‘coolness’ of the film, as you rightly say, sends a dangerous message to young people (like you). Filmmakers should take their role in communicating and constructing contemporary ideologies and views about war much more seriously than they tend to do. Thanks again for your comment!

Excellent analysis!